Tiffiney Tyrrell had her first baby at 15 and her second at 17. The pregnancies disrupted her education and made it difficult to keep a job. Her mother was unsupportive and offered Tiffiney little help in overcoming these challenges. To Tiffiney’s long list of trials was added the devastation of losing her second son before he was two.

Today, the 23-year-old wife and mother has gotten her life back on track: She has resumed her studies and now dreams of attending university. She travels around her country of Guyana and the wider Caribbean, sharing her story with enthralled audiences.

Tiffiney’s life illustrates different aspects of the Caribbean’s struggle with a rate of adolescent pregnancy second only to the poorest parts of Africa. One out of five women in the Caribbean has her first child when she is younger than 19.

Tiffiney was among a group of them who gave testimony earlier this week at the one-day Multi-Stakeholder High Level Consultation on the Reduction of Adolescent Pregnancy in the Caribbean. The event, organised by the UNFPA and the Caribbean Community (CARICOM), was held in Port of Spain, Trinidad, and was a follow up to a CARICOM technical meeting in October in Guyana.

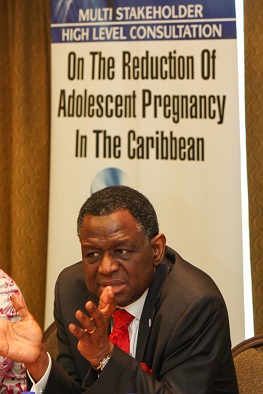

“For all the development that has occurred in the Latin American and Caribbean region, this is one index of development that has refused to go down,” said UNFPA Executive Director Babatunde Osotimehin at the start of the consultation.

“We’ve not been able to shake this because we’ve not addressed it appropriately,” he added.

“Motherhood in Childhood” - the description used through the consultation -is more likely to happen to the poorest and most vulnerable women, making it more difficult for them to improve their economic and social condition and that of their children.

Adolescent pregnancies also affect countries as a whole, depriving them of the full academic and economic potential of the young mothers and creating a situation that perpetuates poverty, unemployment, crime and other social ills.

But there is hope. A number of social programmes supported by the UNFPA, other UN organisations and regional governments have seen great success in getting young mothers trained, educated and employed and in keeping them away from more pregnancies. Some countries in the region have seen recent reductions in their teenage pregnancy rate.

Ten ministers, other government officials, academics, 23 youth representatives and members of NGOs from 15 countries across CARICOM shared good and bad experiences. The meeting was used to fine tune a strategic framework that will guide the region in its continued fight against the problem, which has multiple causes.

One of them is the prevalence of legal child marriages, permitted within certain religious traditions. UNFPA’s Deputy Executive Director, Kate Gilmore, pointed to what she called the “incoherence” in the laws of some Caribbean countries that made it legal in some jurisdictions for girls as young as 12 to marry, set the age of consent as young as 15, yet put limits on the ability of people younger than 18 to get reproductive information and services without parental permission.

“You can be old enough to be a parent but too young to have information,” said Gilmore. “In the Caribbean, laws and policies are creating barriers that increase the vulnerability of adolescent girls.”

Pregnancies among girls under 14 are a particular problem, because they’re more likely to be victims of sexual abuse, more likely to die in childbirth and may be further beyond the reach of social programmes.

“The 16-year-old who gets pregnant people see,” said Osotimehin. “The 12-year-old who gets pregnant we don’t see. People hide them away, and in some cases they marry them away.”

Adolescent pregnancies can have bad economic and social repercussions for a country. Dr. Douglas Slater, CARICOM’s Assistant Secretary General of Human and Social Development, cited research that found countries in the region losing as much as 17% of GDP growth due to the long-term effects of adolescent pregnancy.

The problem has been linked, he said, to poverty, crime, unemployment and other social ills.

“There are also substantial public social and economic costs associated with adolescent childbearing,” he said. “Consequently, reduction in adolescent pregnancy should be viewed not only as a reproductive health issue but as one that works to improve all of the region’s health and socio-economic challenges.”

The facts and figures were sobering, but it may have been the testimonials from young people directly affected by the issue that had the greatest impact on those attending the consultation.

Tiffiney Tyrrell – who had to pause to collect herself many times during her story - received a standing ovation. She described walking to a catering course every day after her first child was born. She had been forced to drop out of school. She got a hard time from employers, losing one job because she was pregnant, another because she had a new baby. When her second son was accidentally injured at home by a relative, medical personnel and police officers treated the poor, young mother dismissively. The child died from his injuries.

As she spoke, those listening covered their mouths or otherwise looked distressed. A few cried.

Tiffiney is in a better position now because of programmes she accessed.

“I have grown,” she said. “Today, I can be a better mother to my child. The infomation I have now I wish I had before.”

Participants were also touched by the story of Belizean Elmer Cornejo, a 22-year-old who had been born to an impoverished 17-year-old mother. She had no choice but to leave her baby with her disapproving and abusive grandmother. Growing up he had been sexually and physically abused by male and female relatives.

“I always said that if my mom could have accessed sexual and reproductive health services in her adolescent years, I would have escaped all the sexual abuses that have scarred my life for ever,” he said.

Elmer is now working with various organisations to promote sexual and reproductive health among youth in his country.

Trinidad and Tobago has had some success in combatting the problem of adolescent pregnancy. The country’s adolescent pregnancy rate has fallen by 17.9 %, said Dr. Fuad Khan, the country’s health minister. He attributed the fall partly to getting information to young people and said there was a need for reproductive education in schools.

“I think a campaign should be done on this matter,” he said to applause.

“If we teach our young people about the social, physical and economic drawbacks of teenage pregnancy, we tend to have a better response in decreasing adolescent pregnancy,” he said.

Access to comprehensive sex education for all adolescent girls and boys is among the main recommendations in the strategic framework discussed at the consultation. Further discussions will take place and improvements made to the document until it is adopted at CARICOM’s next meeting in 2014.